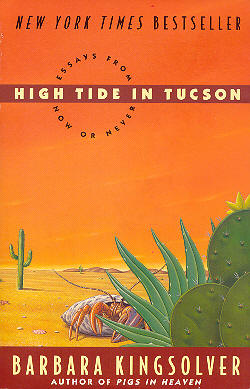

High Tide in Tucson

Barbara Kingsolver

This month, we’re returning to the work of Barbara Kingsolver, resident of Tucson (at least part of each year), and one of this writer’s favorite authors. While Ms. Kingsolver is probably best known for her fiction, she also has a gift for nonfiction; this month’s offering is her book of essays, titled High Tide in Tucson. Subtitled Essays From Now or Never, this volume contains short works of essential truths and much beauty, descriptions of growing up and learning to live in the world we all inhabit; coming to terms with life in general and with her gifts as a writer.

Consider this passage from the essay ‘In Case You Ever Want to Go Home Again:’

“For many, many years I wrote my stories furtively in spiral-bound notebooks, for no other purpose than my own private salvation. But on April 1, 1987, two earthquakes hit my psyche on the same day. First, I brought home my own newborn baby girl from the hospital. Then, a few hours later, I got a call from New York announcing that a large chunk of my writing -- which I’d tentatively pronounced a novel -- was going to be published. This was a spectacular April Fool’s Day. My life has not, since, returned to normal.

For days I nursed my baby and basked in hormonal euphoria, musing occasionally: all this -- and I’m a novelist, too! That, though, seemed a slim accomplishment compared with laboring twenty-four hours to render up the most beautiful new human the earth had yet seen. The book business seemed a terrestrial affair of ink and trees and I didn’t give it much thought.

In time my head cleared and I settled into panic. What had I done? The baby was premeditated, but the book I’d conceived recklessly, in a closet late at night, when the restlessness of my insomniac pregnancy drove me to compulsive verbal intercourse with my own soul. The pages that grew in a stack were somewhat incidental to the process. They contained my highest hopes and keenest pains, and I didn’t think anyone but me would ever see them. I’d bundled the thing up and sent it off to New York in a mad fit of housekeeping, to be done with it. Now it was going to be laid smack out for my mother, my postal clerk, my high school English teacher, anybody in the world who was willing to plunk down $16.95 and walk away with it. To find oneself suddenly published is thrilling -- that is a given. But how appalling it also felt I find hard to describe. Imagine singing at the top of your lungs in the shower as you always do, then one day turning off the water and throwing back the curtain to see there in your bathroom a crowd of people, rapt, with videotape. I wanted to throw a towel over my head.

There was nothing in the novel to incriminate my mother or the postal clerk. I like my mother, plus her record is perfect. My postal clerk I couldn’t vouch for; he has tattoos. But in any event I never put real people into my fiction -- I can’t see the slightest point of that, when I have the alternative of inventing utterly subservient slave-people, whose every detail of appearance and behavior I can bend to serve my theme and plot.”

Kingsolver writes in a lucid, flowing style, carrying the reader along the pathways of her thoughts. Her nonfiction holds the interest of readers in much the same way that her fiction does. In sharing her ideas about the whole business of being alive, Kingsolver as essayist employs the same keen eyes, persuasive tongue, and understanding heart that characterize her wonderful fiction. Be sure to read all about it!

All Rights Reserved.